Orientation

Who cares about philosophy?

When most people hear about philosophy, they think it is:

- Hopelessly abstract

- The opposite of concreate reality

- The opposite of application

- For talking heads who are otherwise inept and clumsy – the wallflowers at a party

- It has no impact on daily life unless we consciously apply it

- It is a philosophical study about lives of old great men, either talking heads or idle dreamers

As we proceed, I hope you will feel differently about philosophy. In my experience, philosophy is one of the most practical subjects to study there is. Why? Because the simplest practical act contains within it assumptions about the nature of reality. Furthermore, a person does not have to have a conscious interest in philosophy in order for that to be operating in their life. Either we choose our philosophy consciously, or it chooses us. If we do not choose it consciously, including the way in which we make meaning, our actions will be out of our control.

I think of philosophy as the skeleton of our thinking process, our infrastructure. If a person has worked out a rough sense of where they stand on the basic philosophical questions, then over time that stance will sink into the plumbing of how they think about any everyday problem. It will seem less and less abstract and closer to everyday life. In other words, the person will see how the choices made in everyday life relate to the abstract philosophical issues. In addition, the individual’s thinking process will be interconnected and more consistent across a wider and wider range of situations. As it stands now most people’s thinking processes are a confused hodge-podge of contradictory platitudes, unexamined assumptions which are often centered around religious belief. But you may say, how do philosophical assumptions get inside the heads of people who have no interest in it?

Every culture must have answers to the fundamental questions regarding the relationship of the group to the larger reality. Part of what makes human life tolerable is the meaning we give to these questions. Now the answers to these big questions have been answered throughout history in various ways. Further, new philosophical questions come into being at different points in history, depending on the general problems a society faces. So I don’t think that philosophical questions are eternal and unanswerable. Over time we develop answers to some questions which are good enough to generate a set of problems for scientists to solve. Cultures that do not develop science answer these questions through mythical stories. Philosophy is not invented voluntarily by smart people.

Every individual living in an industrial capitalist society today has at least partly internalized the philosophical thinking and assumptions of Plato and Aristotle because both Protestant and Catholic theorists have drawn from them. Of course, it is possible to challenge their ontology and epistemology but it takes substantial effort.

My claim

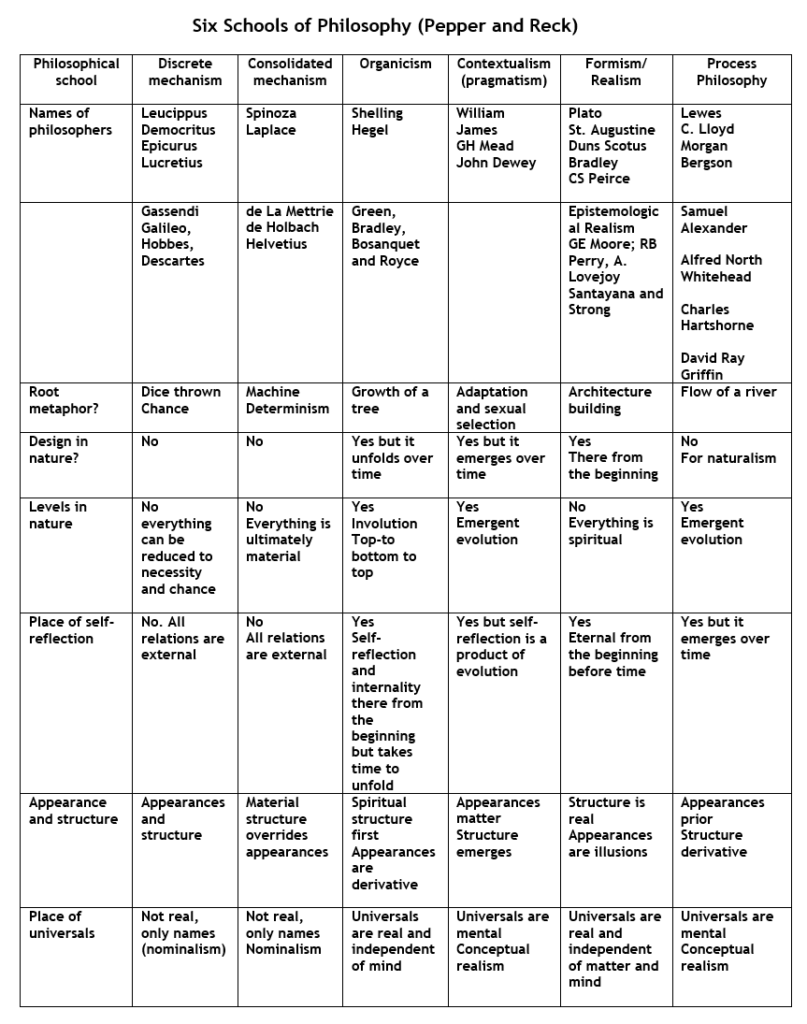

My purpose in this article is to argue that dialectical materialism (which I will refer to as DM) is too narrow in the way it understands the history of philosophy. Typically, it divides the schools into idealist or materialist. Through the work of Stephen Pepper and Andrew Reck I will suggest that the history of philosophy can be better grouped into five schools. These schools will do better justice to the variety of what philosophical ontology has to offer.

Ontological Questions

Ontology deals with the fundamental nature of reality. So let’s look at what these philosophical questions are which every philosophical school must deal with:

- What are we? Are we biological, social or spiritual beings?

- Where do we come from? the earth or the heavens?

- Where are we going? Is there an afterlife or do we die in our graves?

- How is the universe organized? What proportion is designed, improvised, determined or chaotic?

- What is the relationship between mind and matter? Which is primary and which is derived?

- Is the universe good, evil or neither?

- What is the relationship between permanence and change? Which is primary and which is secondary?

- What is the relationship between determinism and free will? To what extent can our actions be controlled?

- What is the nature of time? Is it coexistence with space and matter or does it emerge separately?

- What is the shape of time? Is it cyclical, linear or a spiral?

- What is the nature of space? Is space an empty container for matter? Is it separate from matter? Or is space a qualitative location for magical correspondences such as the zodiac of astrology?

Epistemological Questions

Epistemology answers the question of how we know things. Epistemological questions include the following:

- How trustworthy or untrustworthy are our senses in how we know things? Are they direct reflections of the material world (naïve realism)?

- Are the senses partly accurate and must be refined by reason?

- How trustworthy or untrustworthy is reason in telling us about what is true?

- How trustworthy is mathematics (rationality) in describing to us what is true?

- How trustworthy are our emotions in guiding our understanding of the world?

- Is there such a psychological process such as intuition and if there is how is it different from the senses, reason, rationality, and emotions?

- How trustworthy is a revelation (claims to knowledge that are claimed to come from other worlds)?

Our major focus will be on the ontological schools with some reference to epistemology.

Axiology

The field has to do with the nature of values. These values include morals, ethics and beauty. I will not be addressing this topic in this article.

How Many Philosophical Schools are There?

Since I am a Marxist and I studied how Marxists made sense of philosophy, I was taught to divide all philosophical schools into either idealist or materialist. Over the years I have come to see that this grouping was too stark and narrow. Thanks to the work of Stephen Pepper in his book World Hypothesis his division made more sense to me. He divided philosophical schools into:

- Organicism

- Contextualism

- Formism

- Mechanism

I also found the work of Andrew Reck very helpful. In his book Speculative Philosophy he grouped philosophical schools into:

- Idealism

- Materialism

- Realism

- Process philosophy

Roughly speaking materialism and mechanism have considerable overlap. The same is true between process philosophy and contextualism. There is more moderate overlap between idealism and organicism but there is more difference than in our first two pair. Realism stands roughly midway between materialism and idealism in Reck’s system. Lastly, formism overlaps with realism.

In the following section I will describe the assumptions of each school. I will also compare the schools to each other. For example, I show that mechanism and organicism will have different answers when applied to how each understands the relationship between individual and society. I will also name the philosophers who go with each school. The assumptions for each school will answer most of the ontological questions at the beginning of this article.

Lastly, all philosophical tendencies don’t fit neatly into the schools listed. Schools of thinking such as rationalism, empiricism and skepticism, pragmaticism, or positivism are mixtures of two or three different schools. Rather than add these and raise further complications, for purposes of learning I wanted not to be overly simplistic (materialism vs idealism) or overly complicated. I suspect there will be some inconsistencies in parts. My intention is to give you a rough and ready map so that you can categorize individual philosophers you might be aware of into their proper categories. Once you become aware of the typical responses of some of these great thinkers you will be in a better position to make up your own mind and group the philosophers into schools rather than treat each as individuals.

Mechanical or Atomistic View

Fundamental assumptions

- Entities of things exist prior to their relationships (objects are mutable and self-contained atoms).

- Relations only externally or secondarily define an entity.

- Differences are prior to commonalities.

- Boundaries are prior to connections (freedom is the right to be separate).

- Reductionism is a complex system that can be completely accounted for by analyzing their simple parts. Qualitative relations can be completely understood by quantification.

- There is no design in nature, neither divine or human (all change is due to either rigid determinism or chance or both.

- There is no self-reflection within entities (as opposed to an internally generated feedback system).

- Change is secondary and is not constitutional or necessary. Change is an anomaly or a temporarily disturbance on a more basic state of permanence.

- Linear or cyclic causality. Initial conditions determine the outcome. The past determines the future. This is as opposed to being pulled in the direction of a future goal as in divine or human teleology.

- Change eventually leads to a state of equilibrium or homogeneity. This is opposed to change leading to disequilibrium, accumulation, irreversibility and crisis. From this more complex heterogeneous systems may emerge.

Two forms of Mechanism; discrete and Consolidation

In his book World Hypothesis, Stephen Pepper further divides Mechanism into two parts:

- Discrete

- Consolidated

Discrete mechanism is ruled by chance.

- Things are real only if they have a time and place (as opposed to what is real being hidden or sometime in the future) and grounded on primary qualities such as size, shape, motion, solidity, mass (weight) and number. Secondary qualities such as color, texture, smell and sound are not counted

- Most of the structured features of nature are externally related. These include space from time; every atom from every other atom; every natural law from every other natural law; primary from secondary qualities; names of things from their objects (nominalism).

- Fields of location are primary

- Whatever can be located is real.

- Only particularities exist.

- Atoms are indestructible and eternal.

- Time is an infinite one-dimensional manifestation of externally related locations.

In the history of philosophy examples of discrete mechanism are Leucippus, Democritus, Epicurus and Lucretius from the ancient world of Greece and Rome. Gassendi, Galileo, Hobbes and Descartes are representatives from early modern Europe.

Consolidated mechanism is ruled by determinism

The entire world is internally determined, and machine-like. The structure of space and time is completely determined. Historical examples in the history of Western philosophy include Spinoza, Laplace, De La Mettrie, d’Holbach and Helvetius all from the 17th to the 19th centuries.

Each form of mechanism is called a “mechanical materialism” by Marxian dialectical materialists.

Examples of mechanism at work in understanding the relationship between society and the individual

This contrast will be between mechanical materialism and dialectical materialism. Mechanical materialism is the philosophical position of capitalists.

- Individuals are more than or equal to the sum of social relations.

This is in contrast to the Marxian dialectical materialism which says society is more than the sum of individuals.

- Individuals or families can exist independently of society as in functional or dysfunctional families or healthy or sick individuals.

Dialectical materialists would say that whatever problems there are within the family or individuals they are ultimately grounded in larger social institutions.

- Home is the haven from a heartless society.

Dialectical materialism says that, like Martha and the Vandellas, there is nowhere to run. The only haven is building a heartfelt society.

- The individual’s relation to society is voluntary, accidental and contractual, as in Rousseau’s social contract theory.

For dialectical materialists, individuals’ relation to society, is constitutional, necessary and organic.

- Society exists as a neutral field in which individuals compete to satisfy needs and pursue happiness.

The opposite of this for dialectical materialists is society as a womb which gives birth to individuals through cooperative relations. Competitive relations internal to society are a product of the last 400 years (Macpherson, The Theory of Possessive Individualism).

- Social change only partly impacts individual change.

Dialectical materialists say that social change will dramatically change an individual like whether or not they want this.

- Freedom consists of minimizing external social constraints and maximizing the pursuit of private dreams. Flying “free as a bird”.

What is the opposite of this? It is discovering freedom by acting first within social constraints and then acting on those constraints and expanding them. As Robert Frost said, freedom is moving easily within your harness.

- Human beings cannot shape history since history is the result of only determinism or chance. Only extraordinary individuals can shape history.

For dialectical materialists human beings can shape history, not just extraordinary individuals. However the shaping is mostly unintended and behind our backs. It is possible to design history in the future.

Organic World View

In DM view, the organic view is connected with idealism. For us, most of the organic view of the world is the opposite of mechanism.

Fundamental assumptions of organicism

- Relations within a larger whole define entities.

Objects will change as the whole changes:

- Relations within a larger whole internally define what is an object.

- Commonalities within a larger whole are more important than differences.

- Differences have to do with differences in the entity’s functional role within the whole of which it is a part.

- Connections within a whole are more important than boundaries.

All boundaries are relative and permeable.

- Anti-reductionism – complex systems cannot be completely understood in terms of their parts; qualitative relations cannot be completely understood through quantification.

- There is design in nature. There is a hierarchy of wholes with the supreme spirit at the top.

- Entities grow in self-reflection. They develop self-regulating feedback systems.

- Change of an entity is inevitable and moving towards the self-development of the whole universe

- Reciprocal causality. All entities reciprocally affect each other so that what was once a cause is now an effect. It is the future telos or striving that is the final cause.

- Change inevitably leads to increased differentiation or heterogeneity, increasing expansion and integration with other entities.

Organic worldviews on truth, conflict and evil

- Truth lies in development.

Unlike the mechanist, truth is not to be found in local space and present time.

It is found in ever-widening connections between entities which will occur in some future time.

- Appearances are secondary. What counts is an ever-unfolding unity. This unity is in the process of becoming which is deeper than appearances and is largely hidden.

- The importance of stages. The present state of entities is only a moment of their true identity, which unfolds over time.

- Conflict is secondary. They are understood as either inconsequential or illusions.

- Evil is a product of social or psychological problems. It not ontologically real.

Examples in the history of western philosophy include Schelling, Hegel, Green, Bradley, Bosanquet and Royce.

Contextualism

Contextualism shares with mechanism a materialist outlook, but it is not the reductionist mechanical materialism. In many ways contextualism is the opposite of organicism and it has most in common with process philosophy which I will cover shortly.

Fundamental assumptions of contextualism

- Entities have no essence independent of the situation or context in which they are embedded.

These contexts are not necessarily wholes or systems (in contrast to the organicist view).

- The uniqueness of each context is more valuable to understand than the commonalities between situations

- Anti-reductionism. Elementary analysis can be distortive of the richness of the context

- There will always be elements in the universe which are recalcitrant and will resist organization and integration (unlike the organicist).

- Anti-foundationalist. There is no top or bottom in the universe. The search for either an ultimate material building block (mechanism) or a supreme force at the top (organicism) is fruitless.

- Change is primary and structure is secondary. However, change is not preprogramed in a particular direction as it is in organicism.

- Emergence. Novel events are constantly coming into being that are unpredictable relative to previous structures.

- Improvisation in nature produces more complex levels but these levels are not designed.

- Time is part of the creative process in nature

Time is much more than a tracker of events. Time is part of the events themselves and changes them.

- Reciprocal causality. All contexts reciprocally determine others, but as material, formal or efficient causes. Unlike organicism there are no final causes.

- Truth is present in every local context or situation.

This is opposed to the need to derive natural laws from sensuous events (mechanism).

Neither is truth an end point in development as in organicism.

- Truth lies in its ultimate utility, as successful functioning. Truth is, as William James says, in its consequences, in what works.

Most of the contextualism school comes out of the Yankeedom pragmatists, William James, John Dewey, George Herbert Mead and to some extent, Charles Sanders Peirce.

Realism/Formism

This is the trickiest category of all the schools of philosophy. First, because it is easy to confuse with Organism or Idealism. Secondly, because there is an ontological realism which I will discuss also and an epistemological realism.

Ontological realism

There is an objective world of universals like Platonic forms, typologies, archetypes and templates which exist transcendentally to either the material world or the human mind that seeks to grasp them. Universals can be love, beauty, or truth.

This issue emerged in medieval times over the question of the relationship between the universal and particular things. There were three possible positions:

- Nominalism – only particular things are real. Universals such as fathers or mothers are not as real as sensually detected objects.

- Conceptualism – universals exist, but only as conceptions in the human mind.

Their being is in human mentality. In the natural world there are only individual things.

- Realism – universals have existence beyond particular things or mental constructions of those things. Universals are beyond matter and human minds. They are archetypes or like Plato’s forms.

The main problem of universals is how to connect the particular to the general. Another problem is the relationship between external objects in nature and mental objects. This included the relationship between sense data, perception, representation and ideas. Another problem is the relationship between the mind and the body; that is between mental states and physiological processes.

In the history of philosophy in the ancient world, Plato and St. Augustine are good examples. In the medieval world, Duns Scotus defends realism against nominalism.

Closer to the present, Charles Sanders Peirce was a realist.

Fundamentalist formism or realism assumptions

- What is the relationship between things and form? Form or types exist prior to things.

- What is the relationship between commonalities and differences? Commonalities matter more.

- What is the connection between change and structure? Structure matters more. Change comes out of structure. Change is a sign of imperfection?

- What matters is what is eternal. Time is atemporal (unlike Organicists).

- There is design in nature, but it happens once. This is unlike the Organicists for which design is an ongoing process in nature.

- There are levels in reality, but the levels are there from the beginning. They don’t unfold (Organicist) or emerge (process philosophy).

- Ordering of the levels: descend from the top, down.

- What is the place of self-reflection? Self-reflection is there from the beginning. It is not an unfolding or an emergence.

- Type of causality – final causes, due to purpose at the beginning.

- What is the relationship between appearance and reality? Appearance as surfaces which create illusions (Plato). Reality is invisible, prior to and behind appearances.

- How do we make sense of conflicts? Conflicts are not part of nature as they are with the Contextualists. They are to be explained away as due to ignorance or wrong information. The ultimate reality has no conflicts.

- Epistemological foundations are grounded in externalities, eternal forms (Plato) or Aristotle’s unmoved mover.

- What is the realist theory of truth? Truth is externally found in mathematical equations, geometry, maps, diagrams and formulas. This is opposite to the contextual theory of truth. The latter is operational and is manifested in successful functioning or in concrete consequences.

Epistemological realism

This is directed mostly at Organicists either objective idealists like Hegel or various subjective idealists like Kant or Fichte. Epistemological realism says there is an independent objective world independent from the mind that knows it. When cognition relates knowing minds to objects known or knowable, these objects will always have independence of any mind, human or divine.

Epistemological realism comes close to materialism or mechanism because it implies:

- The independence of biophysical nature.

- The mind does not exist as a substance but rather as a function of the physical organism.

The philosophers who were tenacious examples of epistemological realism were all in the 20th century and included GE Moore; RB Perry, A. Lovejoy; Santayana and Strong.

Process Philosophy

Evolution

In science, the seventeenth century had been the century of physics and astronomy. In the eighteenth century thanks to Lyell, there was the discovery through geology of deep time. With the invention of the microscope, we learned about minuscule organisms. When Darwin began his studies when on the voyage of the Beagle we learned of the vast variety of organisms. But of course, Darwin went much further, first in his discovery of adaptation and sexual selection. Then in 1871 with his book The Descent of Man, the relationship between humanity and the rest of nature was posed without the need for a “Grand Creator” who divinely intervened.

Creativity in time

In the history of philosophy neither mechanical materialists, nor organicists or realists took time seriously. Along with space, it was a container for natural or social events. Marx and Engels were among the first to suggest that human history was a process of class struggle, rather that the frozen events like congresses or wars. Pragmatists in the late 19th century like Charles Sanders Peirce and Chauncey Wright sought to think not just about quantitative change within organic nature but qualitative change that occurred in large scale relationships between matter (the inorganic), life (the organic) and the human mind. Peirce writes that evolution displays three types:

- Tychism – evolution of change

- Anancasm – mechanical necessity

- Agapism – evolution of creative love

It was Henri Bergson who emphasized that “creative evolution” was a never ending process and that static events were temporary thick moments of an effervescence movement the flowed between matter, life and mind.

Immanent vs emergent evolution

In the philosophy of Schelling and Hegel, organicists had their answer. The lower levels of nature were immanent in the higher levels. What happened at the lower levels unfolded from higher forms. Higher forms descended into the lower and brought them up. In the 20th century Teilhard de Chardin and Sri Aurobindo in India continued this tradition.

By what if Bergson was right about creativity of time? Does that mean that instead of evolution being immanent, evolution was emergent? What if the levels of nature emerged from lower levels and there was real novelty in nature? This was the road taken by George Lewes in the mid-19th century and followed up on by British philosopher comparative psychologist C. Lloyd Morgan and by the American philosopher Roy Wood Sellars and to a lesser extent by John Dewey. In the field of social psychology George Herbert Mead showed how society was the next emergent property beyond life and matter.

Process theology

Many see the grandest synthesis of process philosophy in the work of Alfred North Whitehead in his great book Process and Reality. Whitehead did not want to abandon process philosophy to materialists and insisted that God can be seen as a process rather than as a being. Charles Hartshorne learned from Whitehead and added some twists of his own. David Ray Griffin worked to sharpen the work of Hartshorne. Process theologists wanted to unify nature through a kind of panpsychism, without any supernaturalism.

Fundamental assumptions and endeavors of process philosophy

Despite the differences between theological and secular process philosophy we can still identify many principles that unite them:

- Movement and change is the primary reality. It is ongoing independently of human intentions. Structure or form is a derivative of change and not primary as it is with the mechanists.

- It strives to articulate the conditions in which change takes place.

To what extent is it the result of necessity, chance or design?

- It strives to develop a typology of change distinguishing qualitative from quantitative change and distinguishing transitions from crisis.

- It strives to understand the shape of change whether that change is cyclic, linear, non-linear or a spiral.

Are changes oscillations of a primary statis state? Are changes irreversible or reversible?

- To what extent does change accumulate and have consequences?

Process philosophy strives to understand the relationship to time, the past, present and future.

- It strives to understand the levels of change. Process philosophers involve themselves in understanding the relationship between matter, life, mind and society.

- It strives to understand the value of change.

Is change inherently good, progressive and negentropic? Or is change degenerative, and entropic? Is change necessary?

With which other school of philosophy does process philosophy have most in common?

Process philosophy shares most in common with contextualism.

- There are no essences independent of contexts and situations

- Anti-reductionism – there are levels of complexity in nature.

- There are recalcitrant elements in nature which resist organization.

- Anti-foundationalism – change is infinite in space and time.

There is no bottom or top where change ceases.

- Emergence of novel events are constantly happening in the universe.

- Nature is self-regulating through improvisation. Nature creates and recreates herself.

- Time and timing is a constitutional element in this improvisation.

What Can Dialectical Materialism Learn from Mechanism, Organicism, Formism, Contextualism and Process Philosophy?

Mechanism

In trying to integrate DM to the five schools, it’s best to start with mechanism because mechanism starts from the material world, nature. It dismisses any spiritual essences or interventions. At the same time, DM departs from mechanism because mechanism is reductionist. In contrast, DM shares with contextualists and process philosophy a sense of emergent levels in nature. Furthermore, mechanism lacks a sense of self-reflectiveness that characterizes organicism and contextualism. DM shares with mechanism the conviction that what drives natural evolution is necessity and chance. What mechanism misses is that at the level of humanity there is design in nature in that human social plans that can change nature. Lastly mechanism’s sense of matter is that it is dead and externally driven. In DM, as for La Mettrie, matter is dynamic and self-organizing.

Organicism

DM is directly opposed to organicism in its point of departure. Organicism starts with a spiritual whole whether the whole is of Schelling or Hegel. DM begins with matter in motion. It agrees with organicism that there are levels in nature, but it sees these levels as emergent processes, driven from the bottom to the top. Organicism understands levels in nature as unfolding and moving from top to bottom and back to the top. DM agrees with organicism that self-reflection and internality are an important part of nature. Yet, organicists assume self-reflection is built into the cosmos as a whole, right from the beginning. For DM self-reflection is an emergent process which occurs with the rise of social complexity. Self-reflection is not there at the beginning. DM agrees with organicism that internal relations precede things. However, internal relations only apply at certain levels of complexity. Primitive matter does not have internal relations. It is driven by external relations such as natural selection and chance variations. We agree with organicist Hegel that conflict is the mother of all change. However, Hegel’s conflict is too neat and pretty and lacks the “out of control” dimension when conflict is generated outside the system.

Formism/Realism

DM has the least in common with formism for many reasons. We don’t think much of Plato who is probably the most well-known Formist. Like organicists, Formists start with a spiritual essence (Plato’s eternal forms) but unlike organicists Formism lacks a developmental direction that organicists share with DM. Also, unlike organicists time is unimportant to Formists, while it is essential to emergent nature for DM. Formists are opposite to DM in that conflict and change are indicators that something is wrong. In DM both conflict and change are more important that stability or types. We agree with Formists that appearances should not be taken as given. For us, the senses can be deceptive and should not be taken for granted. However for Formists, appearances never tell the truth because they depart from eternal forms. For us, sometimes the senses, corrected by reason are trustworthy. We agree with Formists that structures are important, but for us structures are not transcendental, eternal forms. They are a necessary part of nature but they change, disintegrate and reform.

Contextualism

DM has a great deal in common with contextualism. We appreciate their perspective on situational change, conflicts as foundational in nature and emergence as a property of levels in nature. We applaud its insistence that appearances matter but they often understate the important of structures underneath appearances. DMs are less militant that there are no foundations in nature. Though foundations today keep changing (the nature of subatomic particles) that doesn’t mean it will always be that way. Our main problem with contextualism is that it comes out of a liberal understanding of society. The pragmatists – whether James, Dewey and to a lesser extent Peirce and Mead – see the individual as the basic unit. This applies to its theory of truth – practice and consequences. For DM truth for humans is practice, but social practice. Individual practice is not the test of truth for science. Individuals are far too untrustworthy to measure the truth of something. It is the social practice of science which is a much more reliable test.

Process philosophy

Process philosophy can be broken down into types:

- The naturalistic process philosophy of Heraclitus, Lloyd Morgan and Roy Wood Sellars.

- The process theology of Samuel Alexander, Teilhard de Chardin, Whitehead, Hartshorne and David Ray Griffin

DM has little in common with Chardin’s God or Whitehead’s eternal objects. We would take issue with Hartshorne or David Ray Griffin’s argument that the internality of nature goes very far back. Rather, psyche is emergent in complex human life. However, some of the concepts of Samuel Alexander can be worked into a dialectical framework. For example, Alexander’s slogan “deity is an effort not an accomplishment” is a powerful statement about what matters most is movement rather than things. Alexander’s God is the material world in its totality. This makes Alexander a pantheist god. Furthermore, Chardin’s concept of a noosphere surrounding the earth speaks to the globalization of society and a planetary communist society in the future. I still find Chardin’s description of the growth of the noosphere as breathtaking now as it was to me 50 years ago.

Process philosophy has levels in nature, usually matter, life and mind. DM claims that levels of nature are matter, life (biology) and society, not mind.

Mind is the emergent result of societies that grow to become complex. In addition, process philosophy has no primary place of conflict in its philosophy. Unlike Hegel and Marx, in which conflict is the driver of evolution, for process philosophy if conflict exists at all in nature it is not given a primary place. As Marxists evil for us has no ontological status. Rather it is a derivative of social life under class conditions. For theological process philosophy, evil has an ontological place though their evil has nothing to do with any fundamentalist devil. DM stress the importance of time, not just in philosophy, but in social life such as the preconditions for capitalism and socialism. Both dialectical materialism and process philosophy see nature as self-regularity and immanent.

What’s wrong with dialectical materialism

DM has two forms of idealism – the objective idealism of Plato, Schelling and Hegel and the subjective idealism of Kant and Fichte. However, it makes no distinction between Formists like Plato and Organicists like Hegel and Schelling. Secondly, while the distinction between mechanical materialism and dialectical materialism is good, the difference between discrete and mechanical materialism is not clear enough. Marx’s dissertation of a comparative study between Democritus and Epicurus should have been followed up on. It is my hope that Marxists open up their framework of philosophy to include six types rather than two or three. Please see the table below for a summary of the six schools.